People and markets do not follow set models and theories.

Behavioural financial market theory is an area that was shaped by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, as well as by economist Richard Thaler, who together came up with numerous theories and models to do with behavioural finance. One thing they showed was that different models of theoretical and behavioural economics do not actually exist in real life:

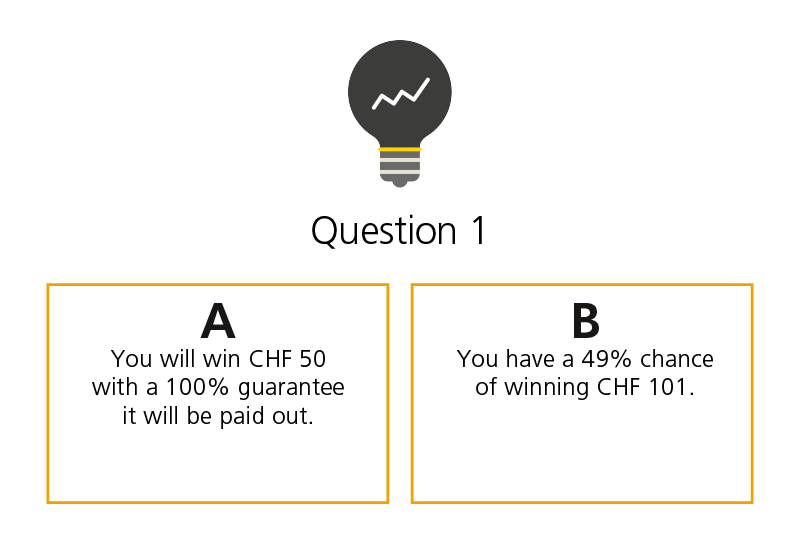

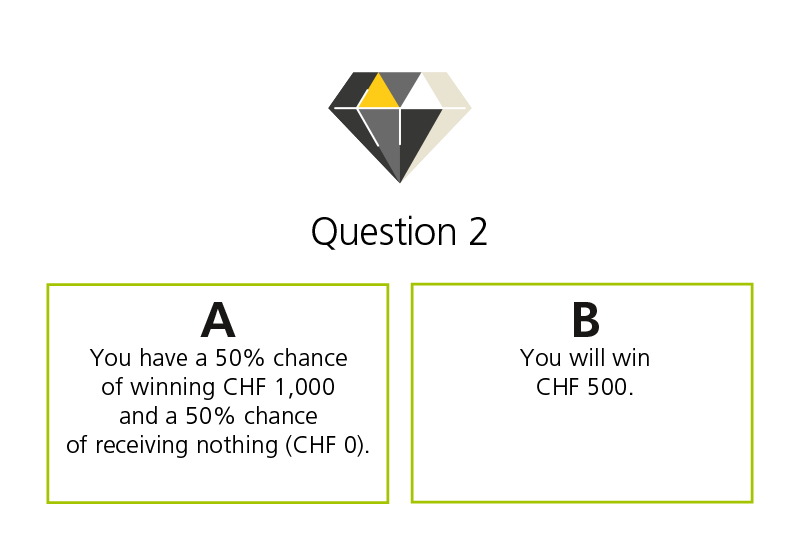

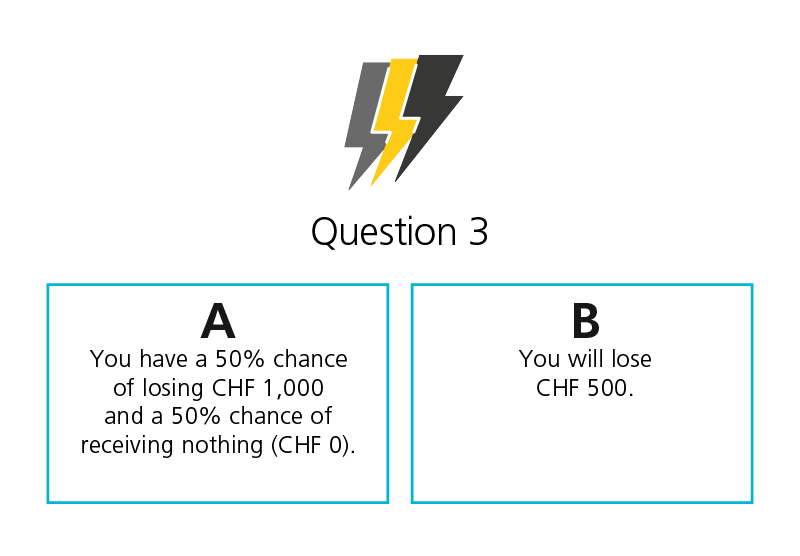

- the fictitious model “Homo oeconomicus” assumes that players in the financial world are completely rational in their actions and are solely motivated by their own interests. The fact is, however, that the decisions people make are not just influenced by rational factors, they are also heavily influenced by irrational behaviour and subconscious actions and patterns.

- In financial theory, reference is often made to the “efficient markets” model (also known as the Efficient Market Hypothesis). According to this theory, financial markets are efficient in the way they work. This means that the prices achieved reflect all the information that is available on these markets. In other words, the hypothesis states it is impossible to make immense profits as a result of a purported information advantage. The trouble is, though, that this only works if investors only ever behave in a rational way. Herd behaviour and panic selling, according to behavioural finance, go to show that people act irrationally on the stock markets. What this means is prices do not always follow an efficient pricing pattern.

In an ideal world where “Homo oeconomicus” and “efficient markets” are the norm, the (completely rational) investors would have all the information available on the market at their disposal, they would be able to classify it flawlessly and use it to draw purely logical conclusions. The fact is, though, that investors behave irrationally, they view certain information as more or less important than it really is, and this leads them to make poor investment decisions. Behavioural financial market theory explains why this is the case – and why it is that these decisions being made over and over again results in supposedly illogical developments on the markets. Investors who recognize these influencing factors and are able to classify them will be able to adjust their strategies accordingly.